Improving Accuracy: A Look at Sums

In the last post on this site, I talked about a project I’m working on called Herbie. Herbie is a project that automatically rewrites numerical program fragments to improve the accuracy of their answers. There’s more background on Herbie in my last post here, and you can check out the Herbie website here to learn all about it.

While we’ve already published a paper on how Herbie can improve the accuracy of floating point expressions, we’re still working on getting Herbie to improve the accuracy of more complex numerical programs, like ones with loops in them. Again, you can check out the last post for more background on this.

In this post, I’ll be talking about a simple type of floating point computation that involves loops, adding up many numbers, and the trick we’re building into Herbie to improve the accuracy of programs that add numbers.

While the basic example, taking a list of numbers that you have in memory and adding them together, seems like a bit of a niche case, it turns out that adding up many numbers is something that shows up a lot in practice. Anytime you’re evaluating a polynomial, multiplying two matrices, simulating a moving object, or many more basic numerical calculations, you’re going to end up adding up many numbers of some form or another. So it’s worth it to know the pitfalls of adding lots of numbers, and how you can avoid them.

A Simple Example

For simplicity, let’s look at a basic example of summing a list, where you’re given a list of numbers, and all you need to do is add them together. Normally, the way you’d do this is to hold on to a variable for your current sum, and then loop through every item in the list, and add it to that variable. At the end, the variable will represent the sum of the entire list.

In Herbie, we represent program fragments as lisp expressions, called s-expressions. So, the c-code that adds our list would look like this:

double sum = 0.0;

for(int i = 0; i < length(input_list); i++){

sum += input_list[i];

}

But we’re going to represent it like this instead:

(do-list ;; This bit of syntax declares that we're looping over a list

([sum 0.0 (+ item s)]) ;; We have one accumulator variable, sum, which starts

;; at zero and gets the next item added to it every time.

([item lst]) ;; We're going to loop across every item in the input list, "lst"

sum) ;; When we're done, we'll return our sum.

This makes it easy for Herbie to mess with the program while it’s looking for more accurate versions, and we’ll be presenting all of our program examples like this from here on out.

You might think that programs as simple as this can’t have much error at all. But adding even as few as a thousand random 64-bit floating point numbers can result in losing almost half the bits in your result from rounding error. Since so many programs use summation in one way or another, this can end up being a serious problem.

While the previous version of Herbie, which only operated on loop free programs, could improve the accuracy of a straight-line summation of a few numbers, without support for loops there’s no way to improve the accuracy of a sum of an arbitrary number of items. Fortunately, once we extend the tool to reason about loops, there is a way we can improve the accuracy of this program. It’s called “compensated summation”. But before we get into the details, let’s go over some background.

A Quick Introduction to Floating Point Sums

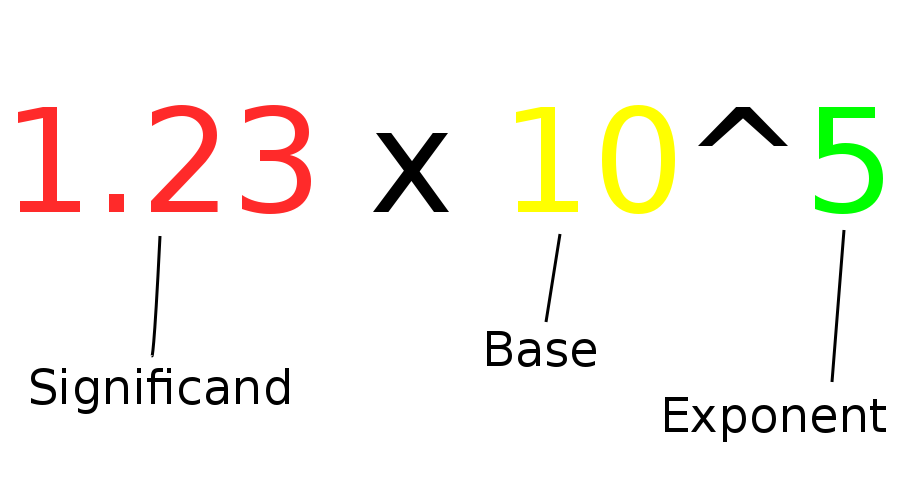

Floating point numbers on computers are represented kind of like the “scientific notation” you might have learned about in high school. In this scientific notation, instead of writing numbers like 123,000, you write them as 1.23x10^5. The part that comes before the multiplication, the 1.23, is called the “significand”. The part that is raised to a power, the ten is called the “base”. And the power itself is called the “exponent”.

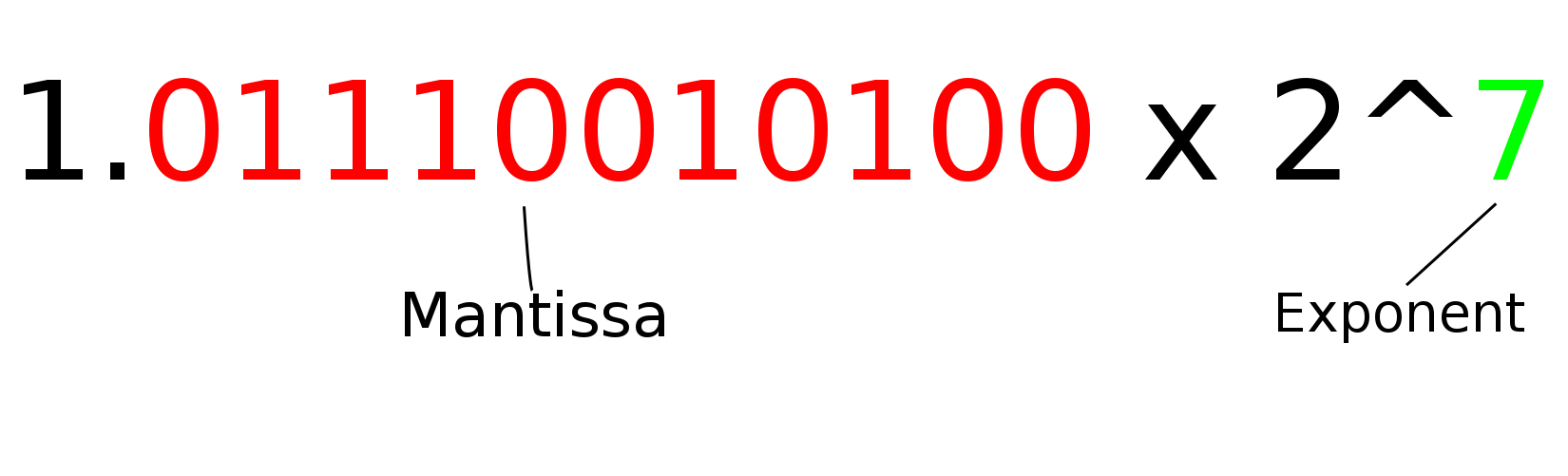

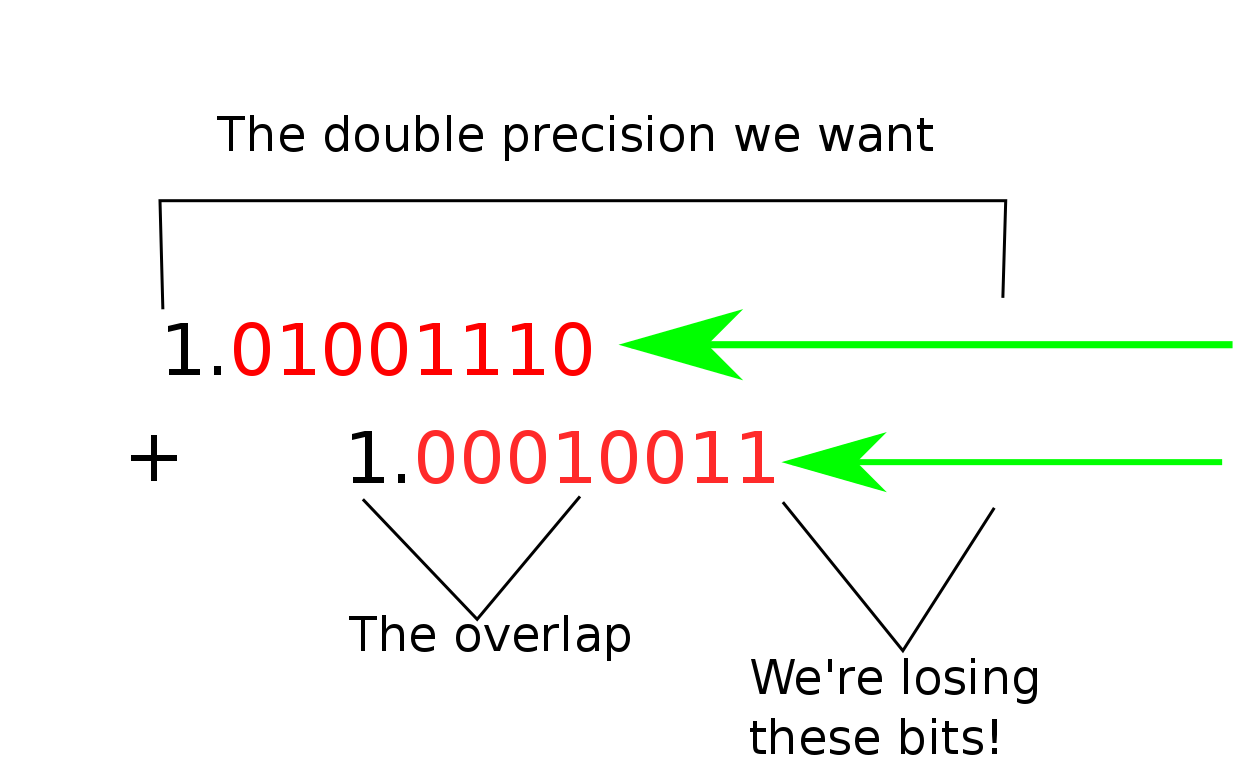

In the floating point numbers that exist on modern computers, the base is two instead of ten. With a base of two, the digit of the significand before the decimal point is always a one (except for some weird cases called subnormals, but we can ignore those for now). So we instead only have to represent the digits after the decimal point, and the exponent. We call these digits after the decimal point the “mantissa”.

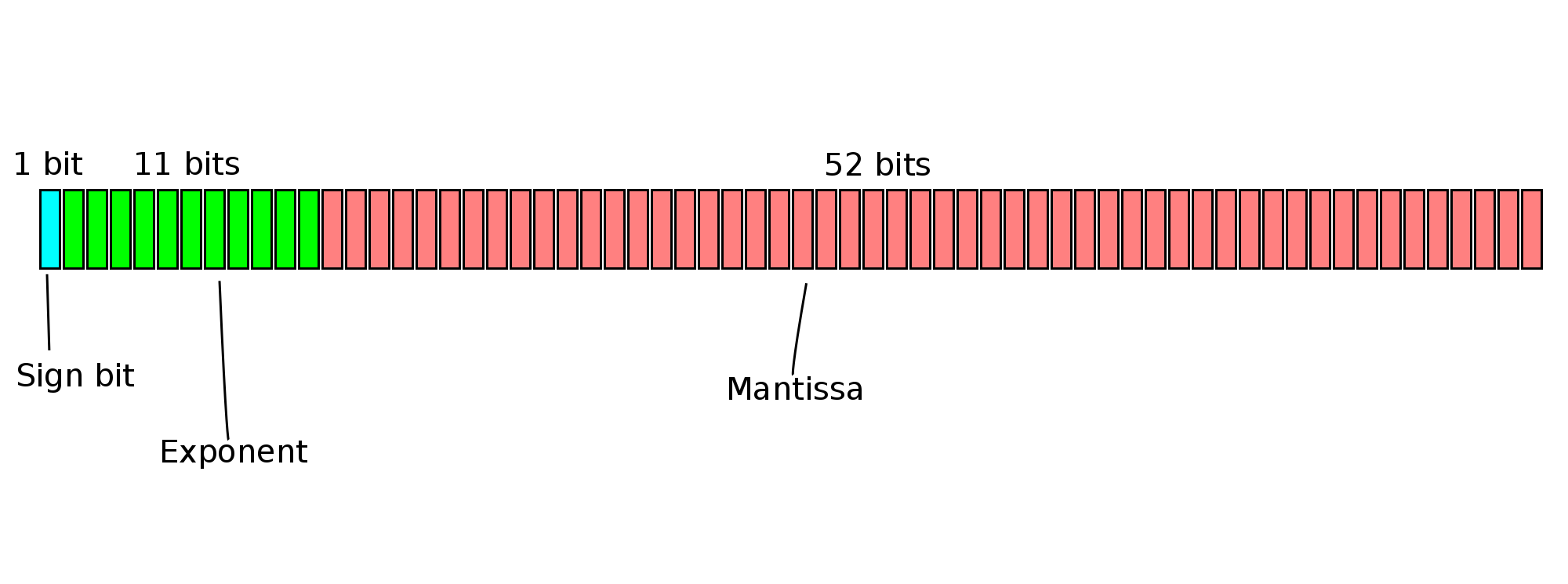

So floating point numbers on computers have some bits to represent the mantissa, some bits to represent the exponent, and some bits to represent the sign (whether the number is positive or negative).

Now, what happens when you add two floating point numbers?

Well, one of two things could happen. One number could be much larger than the other, in which case the result will probably be the same magnitude of the larger number. Otherwise, the numbers could have roughly the same magnitude (or the bigger one could be very close to jumping up an exponent), and the result will have a bigger exponent than both of them.

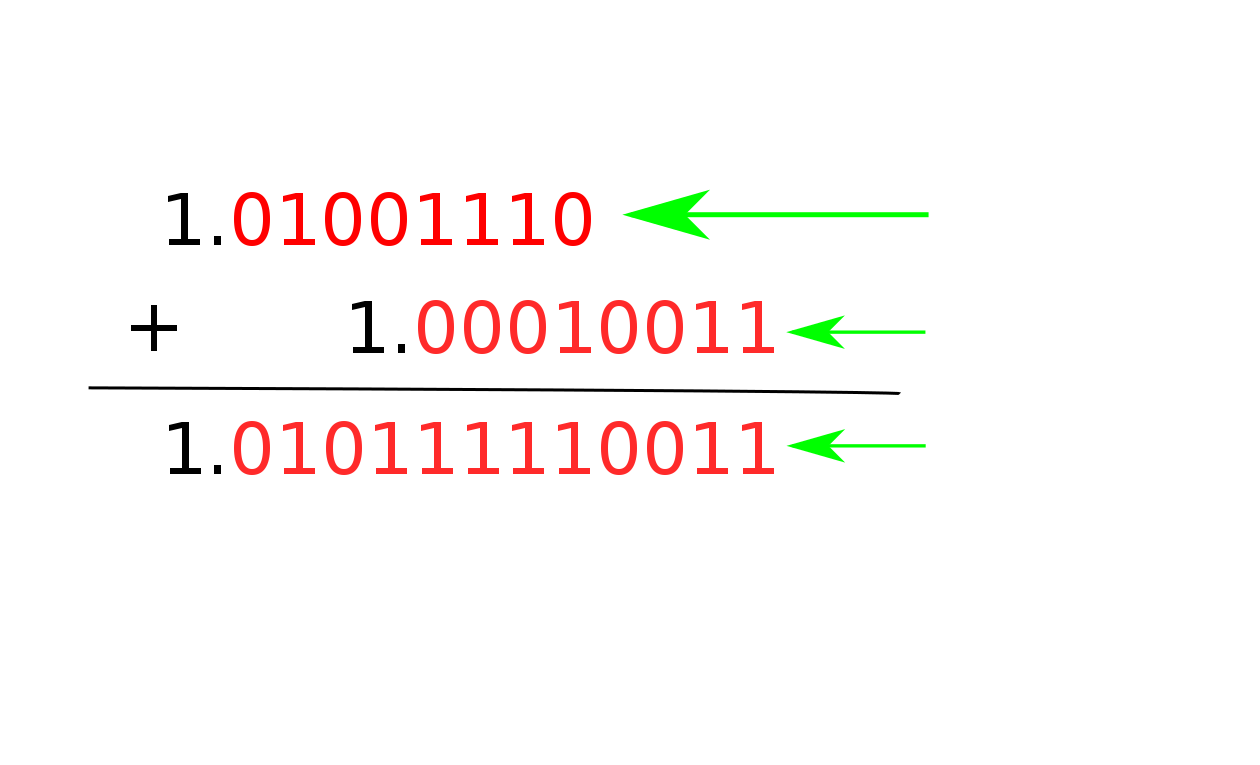

Either way, the result is going to have a bigger exponent than one of the numbers. Since the mantissa only has so many bits, this means that bits on the lower end of the smaller number are no longer going to be in the range that the mantissa represents, and they’ll be dropped off. This is what we call “rounding error”.

In a case like this where we have a single addition, there really isn’t much we can do about this. No matter what we do, those small bits of the number won’t fit in our 64-bit floating point number. And since those bits are so small, we usually don’t care.

The real problem comes when we are adding more than two floats, and the bits that were rounded off add up to enough that they would have affected the final sum. Even when we’re adding a bunch of numbers of the same sign, and the sum is growing pretty fast, the rounded off bits can still grow fast enough to change our final answer. And if some of your numbers are of the opposite sign, the sum might grow much slower than your rounded off bits, and you lose lots of accuracy by rounding off those bits.

Adding a few numbers probably won’t produce enough error to really affect your sum, but when you start summing lots of numbers, it can become a serious problem.

Compensated Summation

The solution to this problem: a trick called “compensated summation.” The Great and Powerful William Kahan introduced this trick in his 1965 article, “Further Remarks on Reducing Truncation Error.” Back then, many computers didn’t support the 64-bit floating point numbers that we have today, and could only use much smaller floats. I wish I could tell you how much smaller, but unfortunately, floating point wasn’t even standardized back then, so different computers had different sizes of floating point. Even back then they ran into sequences numbers they wanted to sum that would lose precision with the size of float they had. Then Kahan came along and wrote about this compensated summation trick that could sum numbers as accurately as if you’d used twice as many bits for your sum variable, and then truncated at the end.

Today, support for 64-bit floats is ubiquitous on our computing devices. But 64-bit floats still aren’t enough to get an accurate sum in lots of cases. Luckily, Kahan’s summation technique can double the precision of your sum no matter how many bits you start with: today, it can make a 64-bit machine look like it used 128 bits for summing.

So, without further ado, let’s dive in and learn about Kahan’s magical compensated summation trick.

How it works

The insight at the heart of compensated summation is to use a second variable, called the error term, to hold the parts of the sum that are too small to fit into our sum variable, but we might want later. Then, when this smaller part gets big enough, we add it back into our running sum. With two variables instead of just one holding on to information about our sum, we effectively double the number of “mantissa” bits we get to use. This means we can be twice as precise about what the value of our sum is, although it doesn’t increase the range of numbers we can hold (that would be the other part of floating point numbers, the “exponent”). Of course, our final answer is going to be a floating point number, so we’re going to have to truncate off this extra precision in the end. But using this trick we won’t lose bits which fit in our extra precision and could have affected the final answer, but were rounded off too early in the original version of the program.

To understand how exactly we get this error term to hold on to the parts of the sum too small to fit into the sum variable, it’s helpful to look at some code. Here is a simple program which adds the items in a list, without any fancy compensated summation:

(do-list ;; This bit of syntax declares that we're looping over a list

([sum 0.0 (+ item s)]) ;; We have one accumulator variable, sum, which starts

;; at zero and gets the next item added to it every time.

([item lst]) ;; We're going to loop across every item in the input list, "lst"

sum) ;; When we're done, we'll return our sum.

Hopefully, this program fragment is pretty easy to understand. Now, to add compensated summation to this, the first thing we’ll want to do is add a error term, which we’ll call “err”. err, like sum, should also start at zero. But how do we update err? Well, err is supposed to hold the parts of the sum that are too small to fit in the sum variable. Let’s do a little bit of math here to figure out what that means.

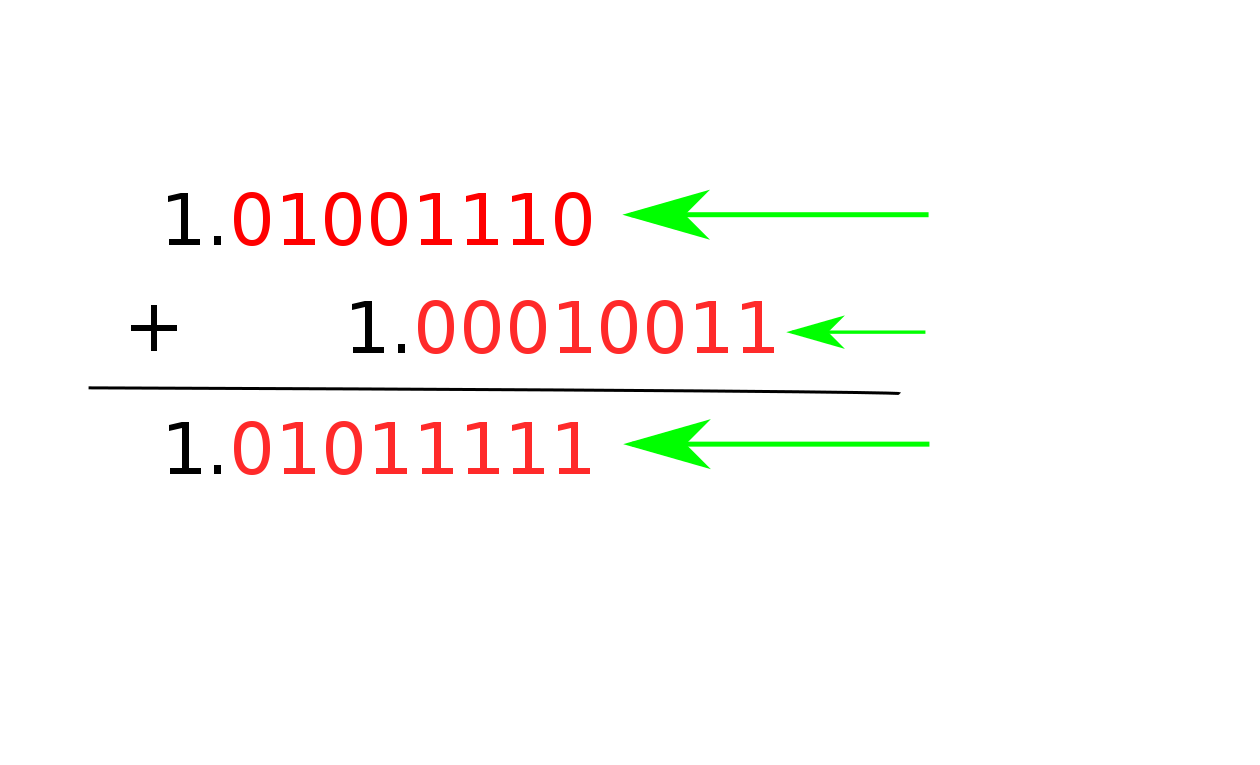

We can say we update our sum with the rule:

\[sum_{i} = sum_{i-1} + item_{i}\]When we add a pretty big number, our old sum, to a smaller number, our current item, we know some error is introduced. If we then subtract the old sum again:

\[(sum_{i-1} + item_i) - sum_{i-1}\]We get a result which is back down to a scale where it can represent the bits that were lost, but since we passed through a big number, we’ve lost them. Now, if we subtract that result from the item:

\[item_i - ((sum_{i-1} + item_i) - sum_{i-1})\]We get the error!

In the real numbers, that formula would always be zero, since we add some things, and then subtract all of the same things. But in floating point numbers, we get the error of the addition. Since we first do the addition, losing some precision as our number gets too big to hold the smaller bits of the item, but then subtract the big part away again, and then subtract the item, we only have the parts of the number that were rounded off.

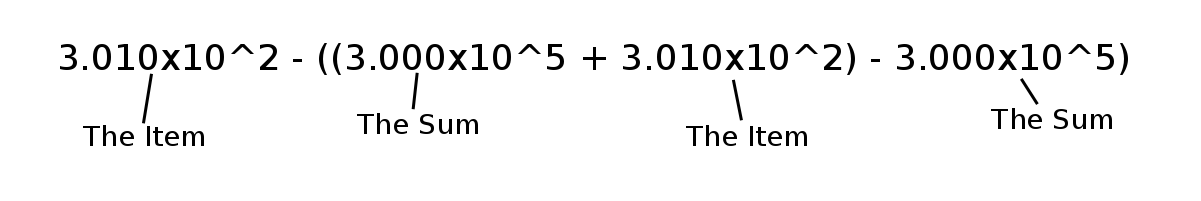

Let’s look at this with an example. Say we’ve got a sum that’s currently 300,000. For simplicity, let’s say that we can only hold 4 digits of precision, so our number is represented 3.000x10^5. Now, let’s say that we’re adding the item 301 (or 3.010x10^2). When we do the addition, we’ll lose the one at the end of our item, since it’s too small to fit in our four digits. The result will be 3.003x10^5, when the real number answer would be 300,301 (or 3.00301x10^5). If we then subtract the old sum away from that, we get 3.003x10^5 - 3.000x10^5 = 3.000x10^2. Finally, subtracting that number from our item gets us 3.010x10^2 - 3.000x10^2 = 1.000x10^0, or 1. That’s exactly the amount that we lost when we added the item to the old sum.

Here we found the error of our computation 3.000x10^5 + 3.01x10^2 with the computation:

Now that we can find the error of each addition, we can keep track of this error and add it in at the end with the program:

(do-list

([sum 0.0 (+ sum item)]

[err 0.0 (+ err (- item (- (+ sum item) sum)))]) ;; Here's where the magic happens

([item lst])

(+ sum err))

This program will significantly improve the accuracy of adding the items of a list over the program we had previously. Yay, we did it!

…but actually, we’re not quite done yet. Even though this program can keep track of more bits of the sum while we’re summing, it can’t yet keep track of twice as many bits as the original. And we can do better.

You see, in this program the error term keeps growing with every addition we do. And eventually, it might get too big to hold some of the bits we care about. In fact, the error term is only useful when some of the bigger parts of it are big enough to fit into the smaller parts of the sum variable that we return at the end. And as soon as it gets that big, it’s precision overlaps with the precision of the sum variable, and it becomes too big to hold the smaller bits of the promised doubled precision. Over time, these bits might have accumulated enough to affect our final sum, so we don’t want to lose them.

So how do we stop our error term from getting too big to hold some of the bits we care about? Instead of only adding in our error term at the end of the loop, let’s add it in every time we go around the loop! If we do this right, every time the error term get’s big enough to overlap with the sum, we can take the part that overlaps and add it into the sum, and the error term will always be a little less than overlapping at the start of the next step. This way, we can always hold on to twice as much precision as either of our accumulator variables (the sum and the error term) could on their own.

To figure out how to do this right, we’ll need some math again. First, let’s look at how our update rule for the sum is going to change. Before, we updated the sum with:

\[sum_i = sum_{i-1} + item_i\]Now, we want to include our error term so far in there, so we’ll update it with:

\[sum_i = sum_{i-1} + item_i + err_{i-1}\]The update rule for our error term get’s a bit trickier, but bear with me. Before, we updated the error term with:

\[err_i = err_{i-1} + (item_i - ((sum_{i-1} + item_i) - sum_{i-1}))\]But now we don’t want to just account for the error in adding the old sum and the item, but also in adding the error term. So we change this to:

\[err_i = err_{i-1} + (item_i - (((sum_{i-1} + item_i + err_{i-1}) - sum_{i-1}) - err_{i-1}))\]We actually don’t need to add in the old error anymore, because the big parts of it are going to be folded into the sum this iteration, so our error term doesn’t need to keep track of them, and the small parts are going to show up in the error of our addition anyway. So, dropping the part where we add the error term from last iteration, we have:

\[err_i = item_i - (((sum_{i-1} + item_i + err_{i-1}) - sum_{i-1}) - err_{i-1})\]If we translate these new update rules back into program form, we get:

(do-list

([sum 0.0 (+ sum (+ item err))]

[err 0.0 (- item (- (- (+ sum (+ item err)) sum) err))])

([item lst])

(+ sum err))

And there you have it! That’s our final program, with the full power of compensated summation. This program will act approximately as if you had a sum variable with twice as many bits, and then at the end you cut off half the bits.

Now that we know how to transform programs which do summation into ones which do compensated summation, it’s fairly straightforward to add this capability to Herbie. We can now finally improve the accuracy of our first loop program fragments. With this technique, we can effectively eliminate the error of programs that add hundreds of numbers. Even more complex programs, like those that calculate the value of a polynomial, can be improved significantly, since many real-world programs make use of adding lots of numbers in one way or another.

With this trick under our belt, we’re well under way to preventing numerical inaccuracy in real-world code.